Geographic atrophy progression

Geographic atrophy is a progression of age-related macular degeneration1

GA is characterised by an irreversible and progressive loss of retinal cells and the underlying retinal structure, including photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choriocapillaris.1–4

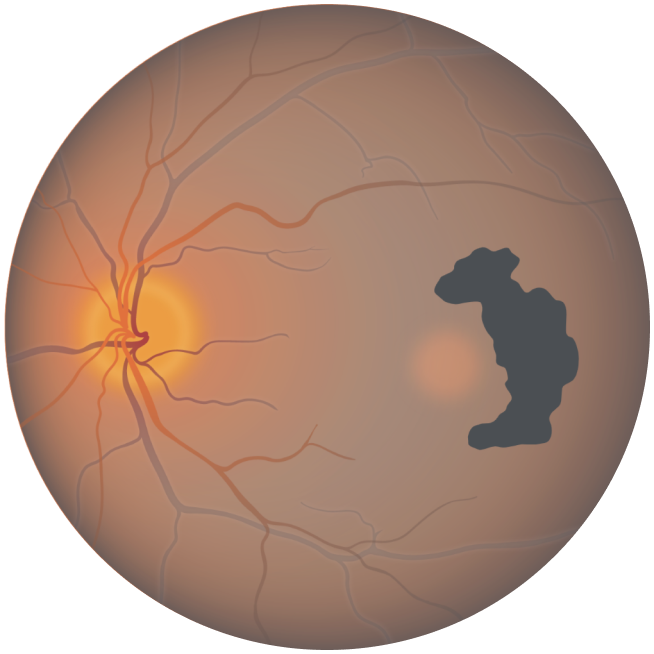

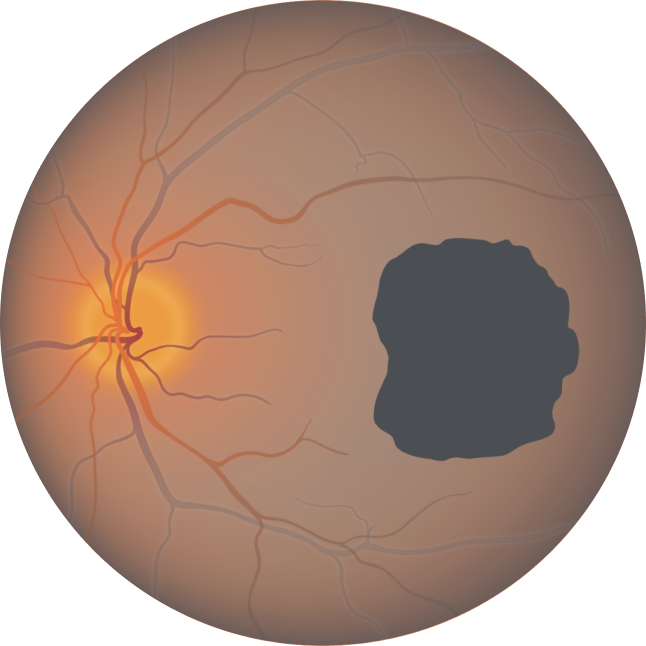

Fundus photograph of a healthy eye

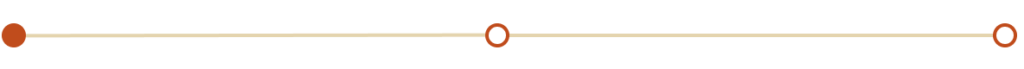

Fundus photograph of an eye with geographic atrophy

Geographic atrophy can sometimes go unrecognised, as vision often isn’t affected until a late stage3,5

Unfortunately, AMD patients often delay seeking help, as they:6

- do not perceive their symptoms as urgent

- believe their symptoms may be caused by a different eye problem

- are unaware of AMD

Patients may assume vision loss is a normal part of ageing and delay seeking help.

It is important to diagnose GA early and monitor patients for progression, so you can help them manage their condition.7

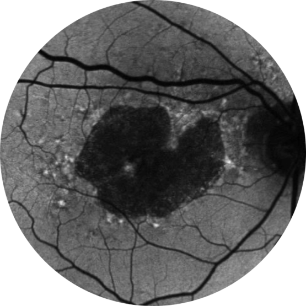

Geographic atrophy progression is constant and irreversible2-5

Areas of damage form characteristic lesions, which typically spread from the non-subfoveal space into the critical subfoveal region.1

While lesion growth in GA may appear to proceed slowly, disease progression is constant and irreversible.

Of the 397 patients who developed central GA, the median time to foveal encroachment was only 2.5 years from diagnosis, according to a prospective AREDS study (N=3640).

Growth of GA lesions leads to visual impairment, even before lesion growth reaches the fovea.

Lesion growth may lead to visual decline2,8,9

Visual acuity does not strongly correlate with geographic atrophy lesion growth.10

However, lesion growth can impact patients’ functional vision, such as reading speed, reading in low light and driving, even before the fovea is lost to GA.1,2,5,11

Around a third of geographic atrophy patients experience a 3-line loss in visual acuity within 2 years and over half experience this decline in 4 years.*5

Eventually, patients experience a permanent loss of vision.1

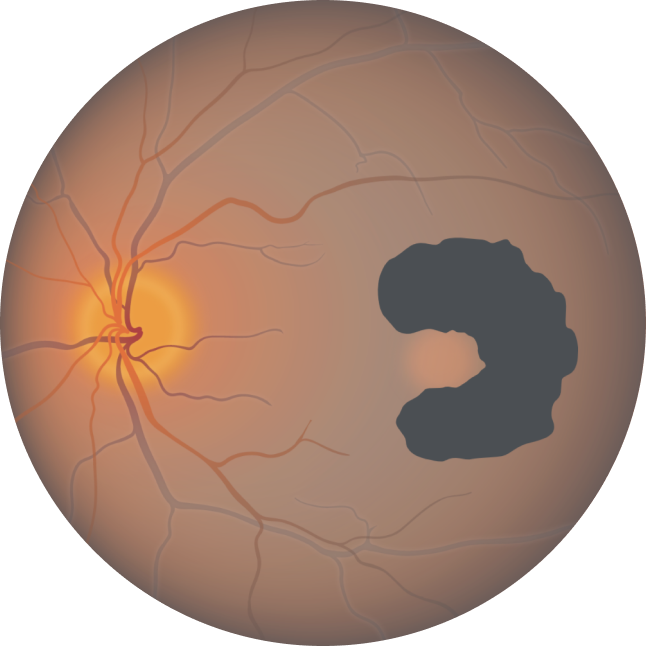

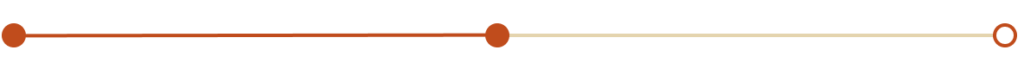

Baseline Year 1

BCVA 20/63+, GA area 5.18 mm2

Baseline Year 2

BCVA 20/80-2, GA area 10.39 mm2

Baseline Year 5

BCVA 20/200, GA area 18.58 mm2

BCVA = Best-corrected visual acuity.

Current management approaches

These approaches focus on coping with the disease, without slowing or stopping lesion growth.12,13

Visual rehab14

Low vision aids15

AREDS supplements16

Smoking cessation16

Exercise17

Diet16

AREDS = Age-Related Eye Disease Study.

AREDS supplements are not an approved therapy for GA.

Therapeutic approaches currently being investigated

To date, there are no approved therapies to reduce the rate of GA progression, although several potential therapies are under investigation.18

Join us on our journey in geographic atrophy

Be the first to receive the latest geographic atrophy news

Thank you for submitting your details.

Please check your inbox for confirmation

What is geographic atrophy?

By 2040, 18 million people may be facing progressive, irreversible, and permanent vision loss.1,19

Patients can lose more than their sight to geographic atrophy

They may have difficulty with independence, relationships, and everyday activities.20–22

Complement overactivation in geographic atrophy

Overactivation of the complement system can be detrimental and is associated with several serious diseases, including geographic atrophy.23

References

- Fleckenstein M, et al. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369–390.

- Boyer DS, et al. Retina. 2017;37(5):819–835.

- Lindblad AS, et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1168–1174.

- Holz FG, et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1079–1091.

- Sunness JS, et al. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271–277.

- Parfitt A, et al. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019;4(1):e000276.

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Age related macular degeneration services: executive summary. 2021. Available at: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AMD-Commissioning-Guidance-Executive-Summary-June-2021.pdf (Accessed June 2023).

- Kimel M, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):6298–6304.

- Sadda SR, et al. Retina. 2016;36(10):1806–1822.

- Heier JS, et al. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(7):673–688.

- Sunness JS, et al. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(9):1480–1488.e2.

- Bandello F, et al. F1000Res. 2017;6:245.

- Sacconi R, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6(1):69–77.

- Ramirez Estudillo JA, et al. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:21.

- Gopalakrishnan S, et al. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(5):886–889.

- Thorell MR, Rosenfeld PJ. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2014;2:20–25.

- Seddon JM, et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(6):785–792.

- Buschini E, et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:563–574.

- Wong WL, et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106–e116 and supplementary appendix.

- Sivaprasad S, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(1):115–124.

- Jones D, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63(7):A0145.

- Apellis & The Harris Poll. 2022. Geographic Atrophy Insights Survey (GAINS).

- Liao DS, et al. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(2):186–195.

EU-GA-2300007 June 2023