When to refer geographic atrophy patients

It is critical to recognise geographic atrophy at first sight

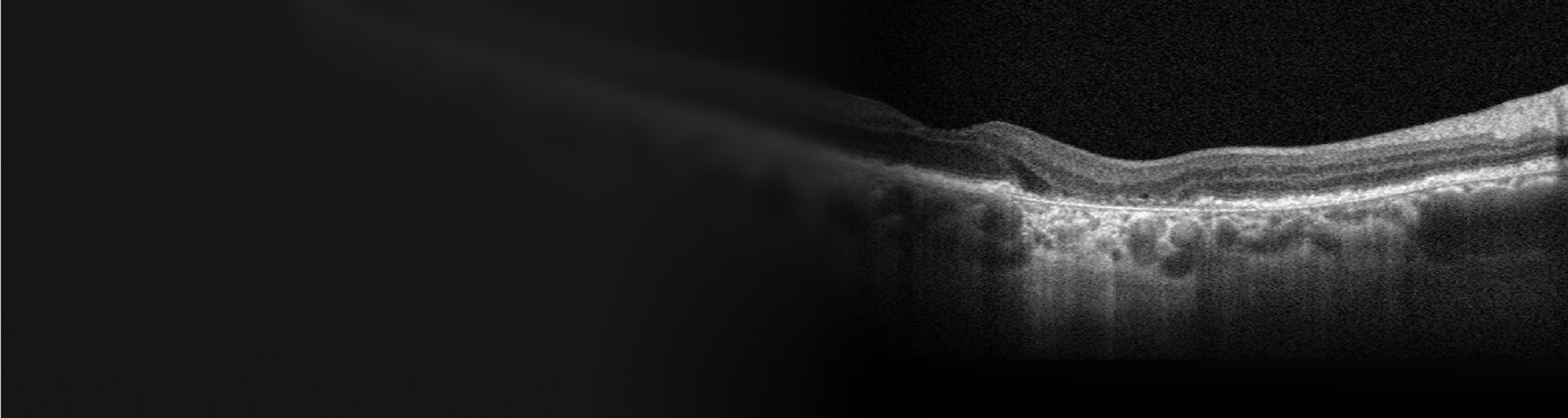

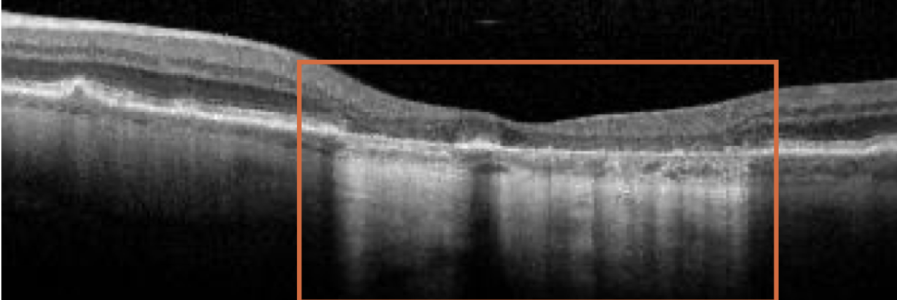

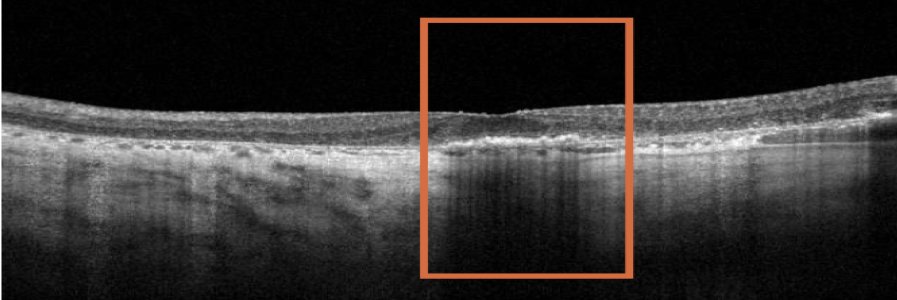

Geographic atrophy is characterised by regions of atrophy, resulting from loss of photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium, and the underlying choriocapillaris. This results in a choroidal hypertransmission defect on Optical Coherence Tomography.1

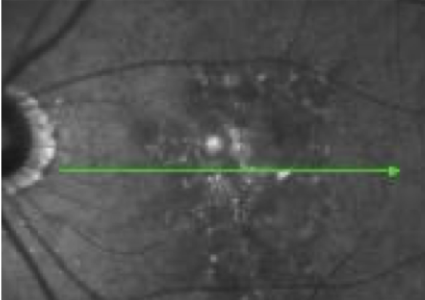

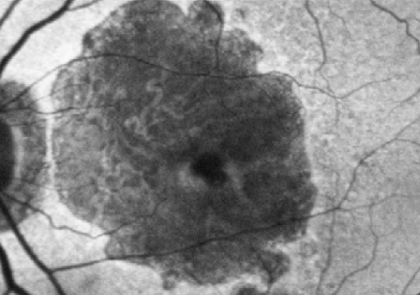

Baseline

BCVA: 6/7.5

Choroidal hypertransmission defect is a sign of atrophy.

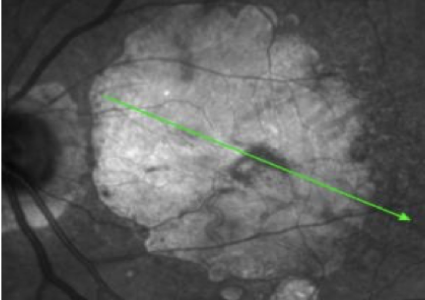

Year 4

BCVA: 6/15

Lesion has grown closer to the fovea as shown by larger area of hypertransmission on OCT. However, BCVA has only declined slightly as fovea is still intact.

Images courtesy of Dr Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, Charles Retina Institute.

Proactively identify patients with geographic atrophy

Ophthalmologists and optometrists play a key role in early detection, monitoring, and timely referral of appropriate GA patients.2

Explore the following patient case studies to see different examples of patients with geographic atrophy who should be referred.

The following case studies employ various imaging techniques for GA, including fundus autofluorescence (FAF), near-infrared reflectance (NIR), and optical coherence tomography (OCT). OS (ocular sinister) refers to an image of the left eye.

GA progression is constant and irreversible1,3–5

Patient case study 1

Edwin G.

75 years old

(Hypothetical patient)

Medical history:

- Family history of AMD

- Former smoker

- BMI 27

- At baseline, patient’s findings are consistent with intermediate dry AMD. Four years later, OS has progressed to GA with foveal involvement

BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/12

- Visual function: Patient is minimally symptomatic with some difficulty seeing at night

FAF

Hyperautofluorescence indicates areas at high risk for atrophy.1

NIR

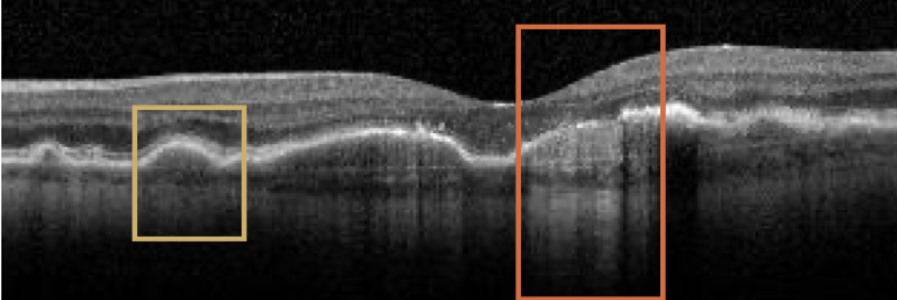

OCT

4 YEARS AFTER BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/45

- Visual function: Patient has stopped driving, and has trouble reading and seeing faces

FAF OS

NIR OS

OCT OS

Large area of atrophy associated with choroidal hypertransmission on OCT

Images courtesy of Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, Charles Retina Institute.

Visual acuity is poorly correlated with lesion size in earlier stages of the disease3,7

Change in visual acuity may not fully capture disease progression;3,7 visual function continues to decline as lesions grow.3,8,9

Patient case study 2

Isabella C.

80 years old

(Hypothetical patient)

Medical history:

- No family history of AMD

- Non-smoker with exposure to second-hand smoke

- Diabetes, hypertension

- BMI 28

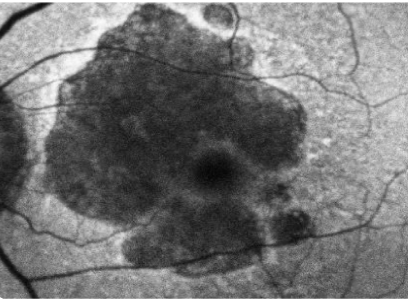

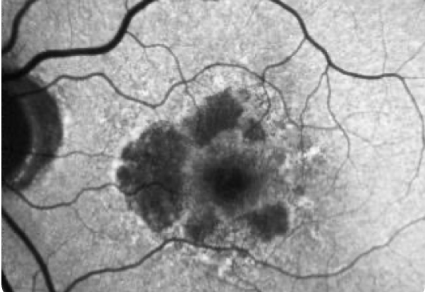

- Patient at baseline has a large area of GA, however, BCVA is relatively unaffected due to foveal sparing

- Within 4 years, OS GA has progressed, but BCVA has only declined slightly as fovea is still intact

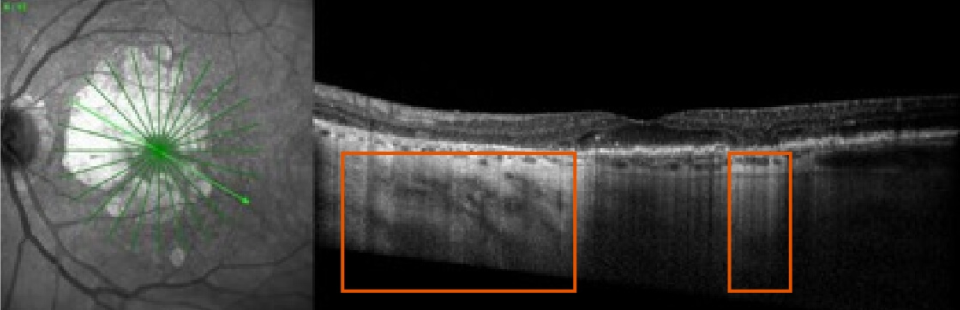

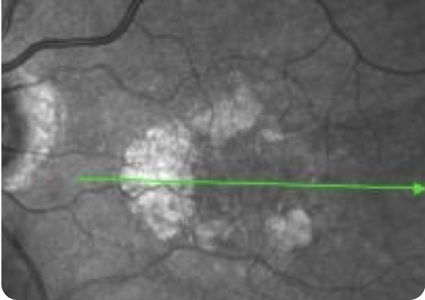

BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/7.5

- Visual function: Patient requires assistance from a caregiver on some activities (eg, cooking, driving), since pericentral vision is lost due to GA

FAF

NIR

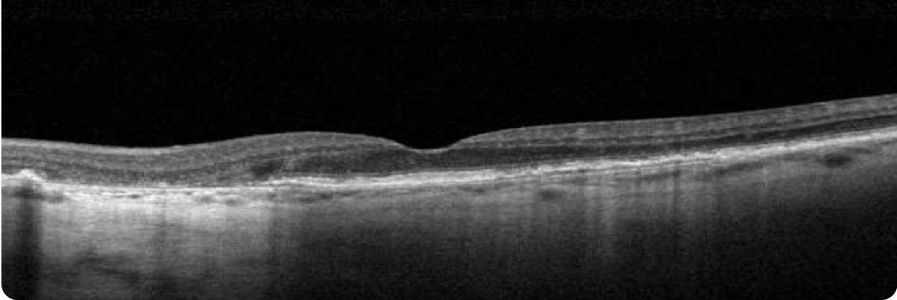

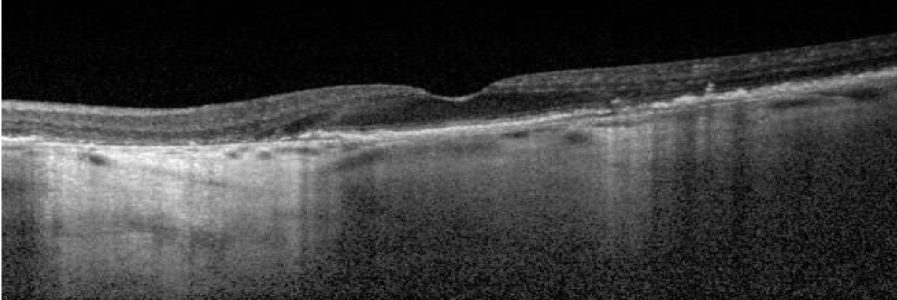

OCT

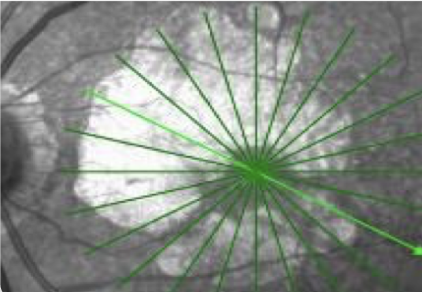

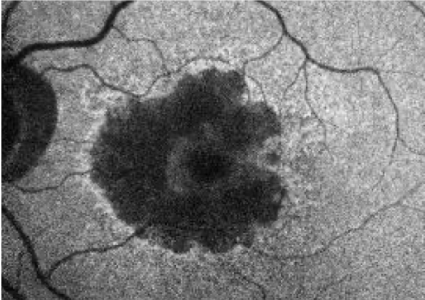

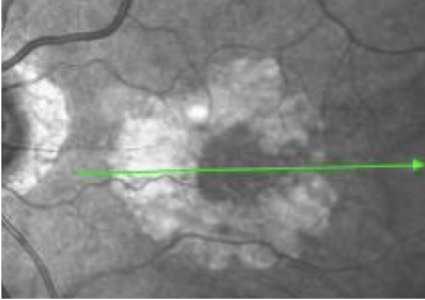

4 YEARS AFTER BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/15

- Visual function: Although patient maintains relatively good BCVA, she has poor visual quality. Patient relies heavily on caregiver for assistance with many activities of daily living

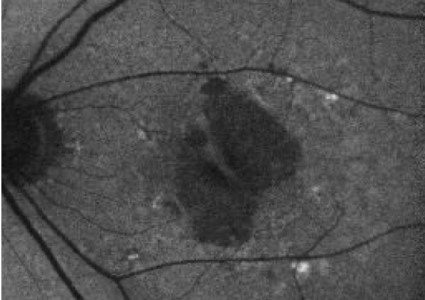

FAF

NIR

OCT

Although there is significant atrophy, the fovea remains relatively spared from GA.

Images courtesy of Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, Charles Retina Institute.

Multifocal configuration, large size, and non-foveal involvement are predictors of faster GA progression1,3,10

Patient case study 3

Carla L.

82 years old

(Hypothetical patient)

Medical history:

- Family history of AMD

- Former smoker

- Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia

- BMI 33

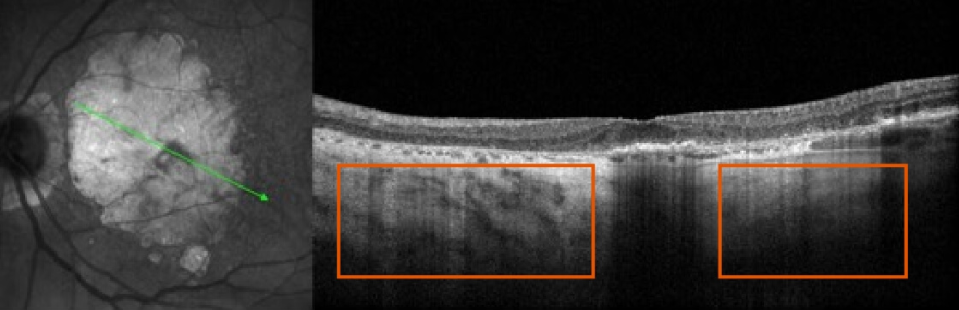

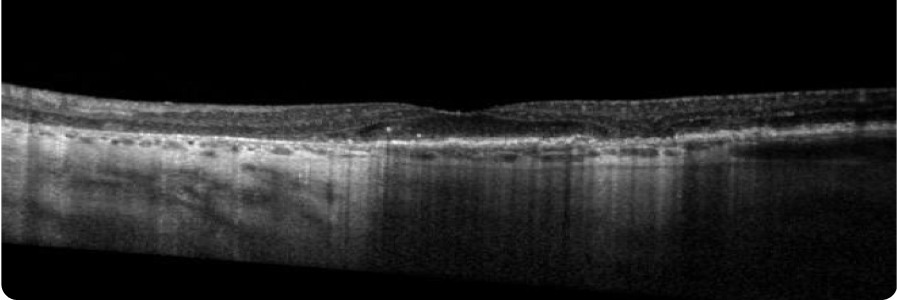

- Patient has GA with multifocal lesions outside the fovea at baseline. These lesions tend to progress faster than unifocal, foveal lesions

- Within 2 years, the areas of atrophy have grown and coalesced. However, the fovea still remains intact resulting in mild alteration of BCVA

BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/9

- Visual function: Patient has dark adaptation issues and some difficulty reading

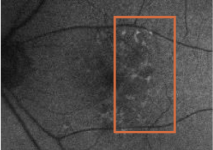

FAF

NIR

OCT

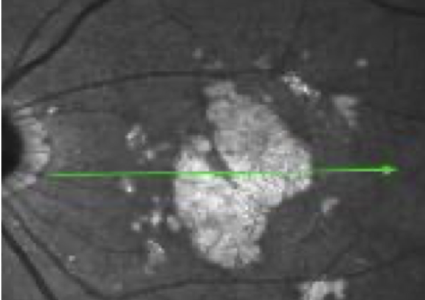

2 YEARS AFTER BASELINE VISIT

- BCVA: 6/12

- Visual function: Patient no longer feels comfortable driving although she is legally able to. Patient relies heavily on assistance from caregiver with some activities of daily living

FAF

Clear progression of perifoveal GA two years later.

NIR

OCT

Images courtesy of Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, Charles Retina Institute.

Access all three case studies below

Join us on our journey in geographic atrophy

Be the first to receive the latest geographic atrophy news

Thank you for submitting your details.

Please check your inbox for confirmation

What is geographic atrophy?

By 2040, 18 million people may be facing progressive, irreversible, and permanent vision loss.1,11

Geographic atrophy progression is constant and irreversible

While lesion growth in geographic atrophy may appear to proceed slowly, disease progression is constant and irreversible.3–5,12

Patients can lose more than their sight to geographic atrophy

They may have difficulty with independence, relationships, and everyday activities.13–15

References

- Fleckenstein M, et al. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):369–390.

- American Optometric Association. Comprehensive adult eye and vision examination. 2015. Available at: https://www.aoa.org/documents/EBO/Comprehensive_Adult_Eye_and_Vision%20QRG.pdf (accessed June 2023).

- Boyer DS, et al. Retina. 2017;37(5):819–835.

- Lindblad AS, et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1168–1174.

- Holz FG, et al. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1079–1091.

- Shijo T, et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4715.

- Heier JS, et al. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(7):673–688.

- Kimel M, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):6298–6304.

- Sadda SR, et al. Retina. 2016;36(10):1806–1822.

- Wang J, Ying G. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64(2):205–215.

- Wong WL, et al. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106–e116 and supplementary appendix.

- Sunness JS, et al. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):271–277.

- Sivaprasad S, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(1):115–124.

- Jones D, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63(7):A0145.

- Apellis & The Harris Poll. 2022. Geographic Atrophy Insights Survey (GAINS).

EU-GA-2300007 June 2023